COUP STUDY 002

This is another edition of COUP STUDY, a recurring roundup of art-related notes, lingering thoughts, and media I consume in between my longform writing and artmaking. The series’ title is inspired by Alison Saar’s similarly titled 2006 charcoal drawing that served as a draft for an eventual sculpture, which makes central a seated woman bound to an amalgamation of suitcases by her braided hair. The finished sculpture consisted of wood, wire, tin, and other found objects, as is common in Saar’s work. For me, COUP STUDY is a collection of what precedes my first drafts—studies—of the little things that inspire my day-to-day. Artistic “baggage” of sorts that I carry with me, and that pique my interest and embed themselves in my psyche even if my engagement with them is fleeting. Additionally, this series is a way for me to share with you all the plethora of Black archival material, my found objects, that circulate in my orbit. Because these are mere notes, I may not always explain them fully or eloquently, and they might not even make sense by the time I post them here, but hopefully, they will inspire you, too.

During the Italian Renaissance, artists among the likes of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Pietro Torrigiano, and Michelangelo were the center of paragone, a debate classifying painting and sculpture as art forms superior and distinct from each other. Medium, form, and skill coincided to shape a broader concept of artistic mastery as sculptors working with materials such as marble, bronze, and terracotta were praised for handiwork that imitated the lively stroke of a paintbrush while casting their subjects into aesthetic immortality. Transcending the talent for replicating human likeness was the goal, surpassing the notion of mere representation through painting. But the line of demarcation between the two forms becomes blurry, of course, as all artistic mediums speak and dance with each other when at the whim of an artist’s hand.

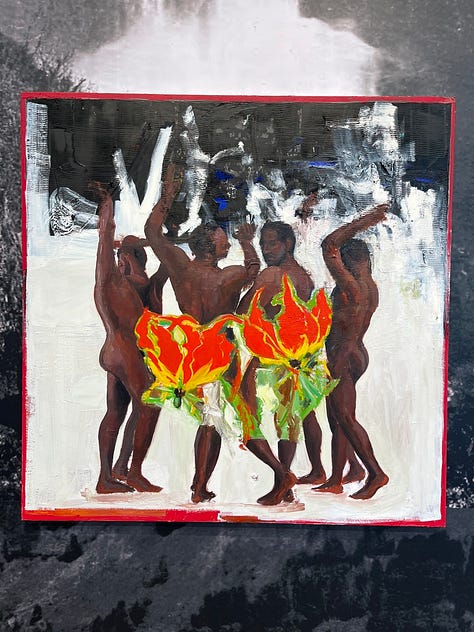

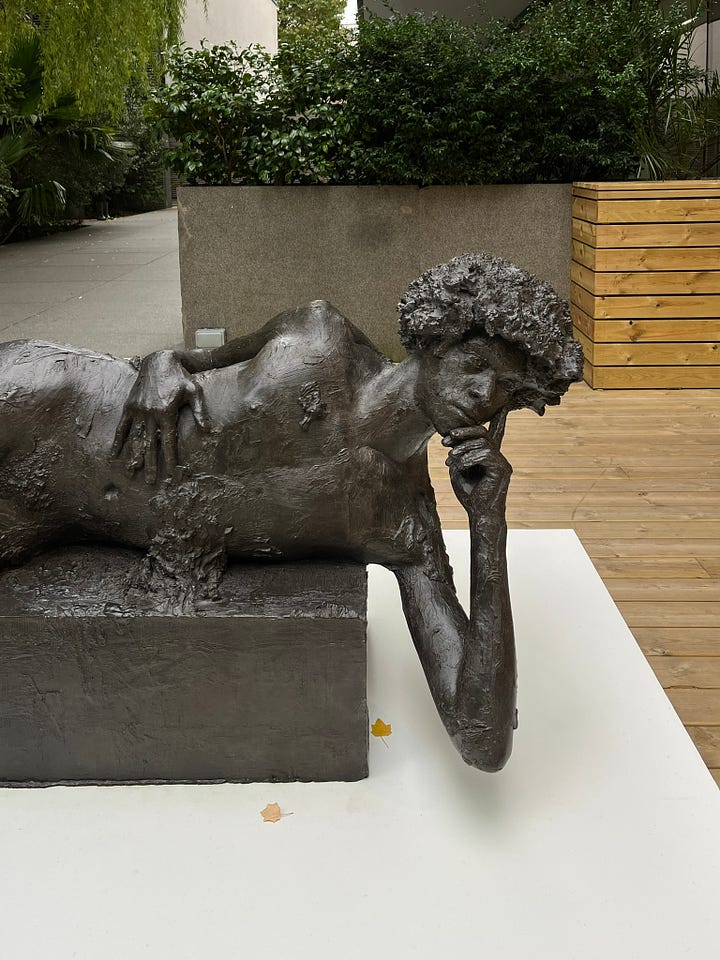

London-based Zimbabwean artist Kudzanai-Violet Hwami, someone whom I’ve long admired for their figurative paintings, debuted their first series of bronze sculptures in their solo exhibition Incantations at Victoria Miro gallery in London, which I was able to see earlier this month. Hwami’s paintings and printed works in the show deal most potently with the construction and fragmentation of a sense of self and identity amongst systems of enclosure. What Hwami also considers is the self between realms of reality and other worlds, mixing personal and archival photographic references with imagery of Greek myth and the supernatural. Scenes of family in Zimbabwe and South Africa, and Black queer bodies in a gathering share space with the philosophical narratives of Persephone or fallen angels. Hwami’s paintings are totems that ask, What is real? And what remains?

You’ll see that from a technical standpoint, Hwami’s paintings read with a silky smooth quality: rich colors that blend but do not muddle, faces that look like kin, and a composition that leaves you curious but not confused. Here are some of my favorites:

Upon seeing Hwami’s new sculptures, though, I was pleasantly met with the same smoothness. The darkskinned, nude figures were formed with the same sweet seamlessness, as if she simply brought one of her paintings to life. A closer look reveals bodies unfinished, or maybe bodies in an act of undoing, as hardened bronze spillage finds itself on the sculptures’ kneecaps, waist, shoulder, and other inconspicuous areas. The evidence of Hwami’s hands trained by a paintbrush, but finding a new home, adds a beautiful texture to these reflective beings.

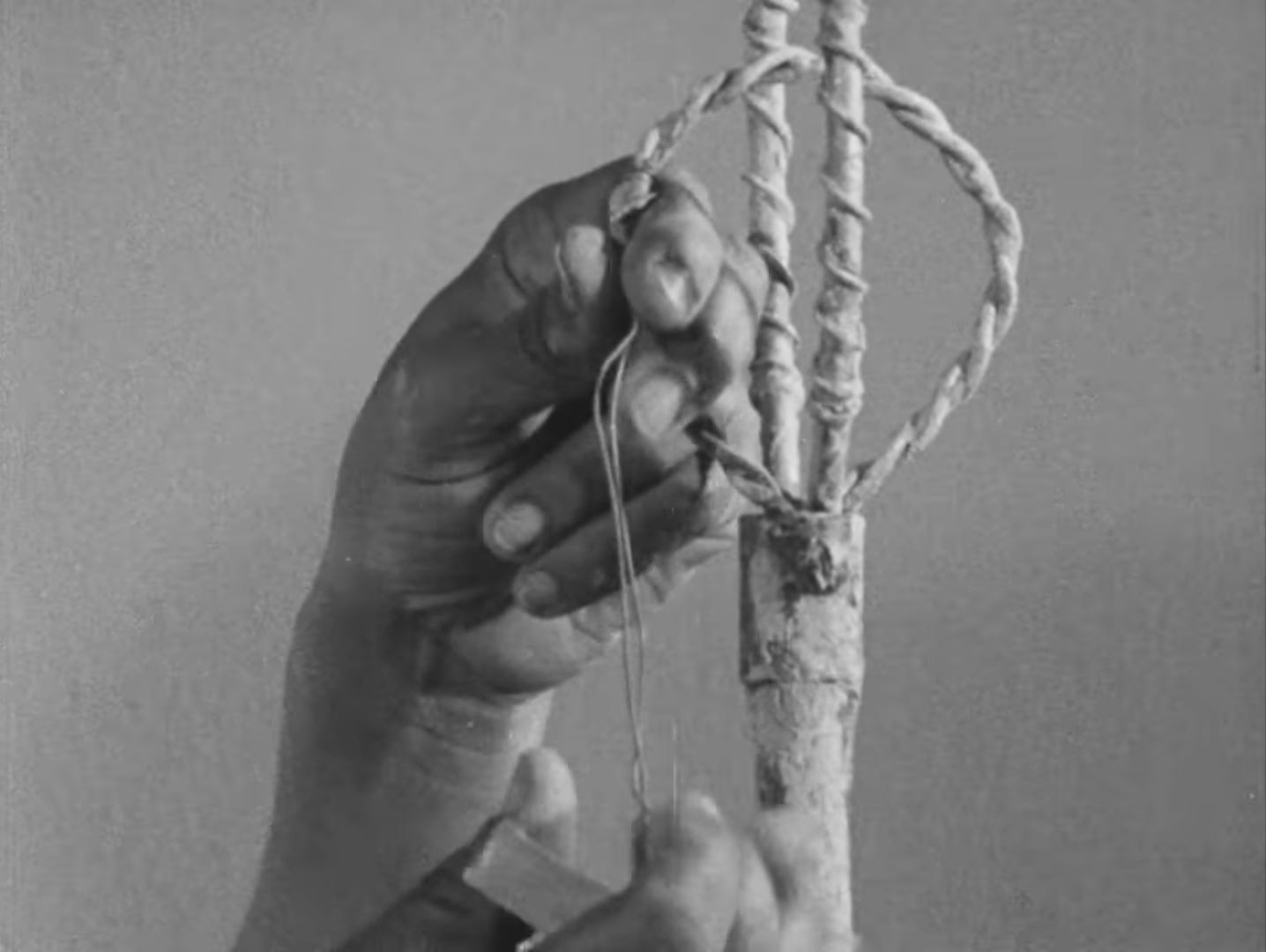

I’ve been thinking about sculpture a lot recently, especially after seeing the exhibition Nancy Elizabeth Prophet: I Will Not Bend an Inch at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in the summer, and seeing one of Simone Leigh’s works in person for the very first time at Tate Modern. There’s a winding lineage of Black women, specifically, in large-scale sculpture and ceramics, and what was held in the hands of each artist who made their hands a prized instrument.

In 1962, director John W. Fletcher Jr. created a short documentary film about actress and sculptor Ruth Inge Hardison, best known for “Negro Giants in History,” her important series of busts made during the early 1960s. In the film, titled Hands of Inge, Fletcher is up close and personal in Hardison’s studio and process, showing her handling clay and sculpting a bust of her daughter. Hardison brandishes sculpting tools like divine weaponry, displaying them almost as if she were casting a spell. Each tool is a way of self-cataloguing. An incantation of her own. I think about this film here with Hwami’s work because sculpting is a very literal act of fragmentation of material, of undoing and unmaking a thing, setting fire to an image to freeze it in what it once was. The film plays like a ritual, where the hands of a Black woman artist are the most ceremonial.

Relatedly, I’d recommend watching A Study of Negro Artists (1936), a black and white silent film that was created to highlight the development of African-American fine arts. The film features many influential Harlem Renaissance artists as well.

I attended a Black queer zine-making event at the Barbican library, and learned so much more about Black queer history in Britain and specifically, how Black queer media in the UK has evolved. Through the British Film Institute (BFI) Player, the other attendees and I watched snippets of Black queer films largely made in the ‘90s. One of those films was Campbell X’s BD Women (1994), a 1920s love story between a jazz singer and her butch lover, interspersed with documentary interviews with contemporary black lesbians. I was enamored by the clip we saw, especially after learning that the film was also inspired by the Harlem Renaissance, but I have not been able to find the film on BFI Player or anywhere else since the event (if any of you have any luck, please let me know). For now, here are some stills:

Here in London, I’m studying at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), which has an extensive collection of art books and publications related to Africa and the diaspora. Some books I checked out this week that I’m excited to read:

Black Earth Rising: Colonialism and Climate Change in Contemporary Art by Ekow Eshun

Daughters of the Dust by Julie Dash (a continuation of her acclaimed film)

Black Orpheus: An Anthology of African and Afro-American Prose by Ulli Beier

Last but not least, I just finished Ekow Eshun’s The Strangers: Five Extraordinary Black Men and the Worlds That Made Them, and while I’m still gathering my words to properly show my appreciation for this book, all I can say for now is that I love creative nonfiction, and Eshun so wonderfully captures that strangely Black feeling of being the world’s stranger. I’ll be reading James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son soon, too, and I expect the two books won’t be too far from each other.

Until then —

With love and gratitude,

G.

the strokes on the sculptures show such a layered effort of the artist Hwami; this exhibit is amazing

Phenomenal work