COUP STUDY 003

This is another edition of COUP STUDY, a recurring roundup of art-related notes, lingering thoughts, and media I consume in between my longform writing and artmaking. The series’ title is inspired by Alison Saar’s similarly titled 2006 charcoal drawing that served as a draft for an eventual sculpture, which makes central a seated woman bound to an amalgamation of suitcases by her braided hair. The finished sculpture consisted of wood, wire, tin, and other found objects, as is common in Saar’s work. For me, COUP STUDY is a collection of what precedes my first drafts—studies—of the little things that inspire my day-to-day. Artistic “baggage” of sorts that I carry with me, and that pique my interest and embed themselves in my psyche even if my engagement with them is fleeting. Additionally, this series is a way for me to share with you all the plethora of Black archival material, my found objects, that circulate in my orbit. Because these are mere notes, I may not always explain them fully or eloquently, and they might not even make sense by the time I post them here, but hopefully, they will inspire you, too.

The peculiar hazy mist of London has greeted me more often than not as winter comes around the corner. I prepare for the cold and rain with a coat and umbrella, of course, but also by nourishing my predilection for internal silence. To sit and watch and wait and take in the sounds and images surrounding me, slowly. You’ll see that I’ve been doing exactly that.

Toward the end of Novemer, the Camden Art Centre held a screening of the film Baldwin’s N*gger (1969) (a documentary by Black British filmmaker Horace Ové which captures a conversation between James Baldwin and Dick Gregory at London’s West Indian Students’ Centre) and a public listening session of an experimental jazz piece by Neil Charles, Mark Sander, and Cleveland Watkiss inspired by Baldwin’s short essay collection Dark Days.

In the film, Baldwin speaks to a crowd of young and curious, perhaps anxious and disillusioned, students, mulling over the state and identity of Blackness in both America and Europe: “They’ve always known that you were not a mule [...] the threat of the whip… the threat of the gun… and the Bible”; “... the white/ Christian/ European/ Industrial drama”; “In the Western house [the Negro is] the most despised child… flesh of flesh, bone of bone… created by them”; “... the flesh is all you have”; “As a Black man I’m compelled to try to create my history…”

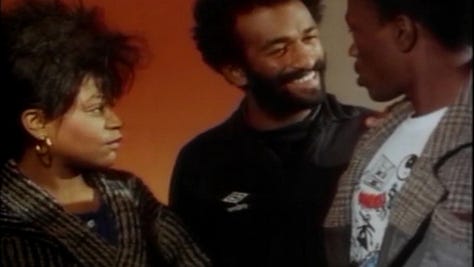

While Baldwin spoke his wisdom and answered questions about Afro-Caribbean futures in the West, the camera panned to the crowd. Black faces overwhelmed the frame, a few even becoming spotlights of character. A man hit his cigarette coolly every time the camera landed on him, returning at least four or five times over to his suave demeanor. A woman sits in sophistication, a bandana hanging over a smooth bang; she seems to be one of the few Black women in the audience for rows and rows.

I was appreciating the various displays of style and poise on the wall projection when a bright, flashing light centered on the wall like a sniper’s target. An older woman in the front row began recording the film and snapping pictures on an even older digital camera. A friend of mine and I exchanged looks as the red flash kept appearing in short increments, sometimes directly on Baldwin’s face and chest. A target he seemed, indeed. The rest of the crowd began to react silently, turning toward the woman to alert her, nonverbally, of her disturbance, but it appeared that she was none the wiser. Maybe she wanted to document the film for her personal archive, send it to a friend, or just watch it later in the comfort of her home beyond the big screen. Whatever the case may be, I couldn’t shake a few things: the camera, in this instance, was a sort of weapon interrupting the show of Blackness before us; the camera was in the hands of a non-Black audience member in a more populated non-Black audience of people attending the screening; and every time that red flash did its duty, the fabulated audience of Black characters in the documentary seemed to make eye contact with us—breaking the fourth wall with their watching, interrogating, warning.

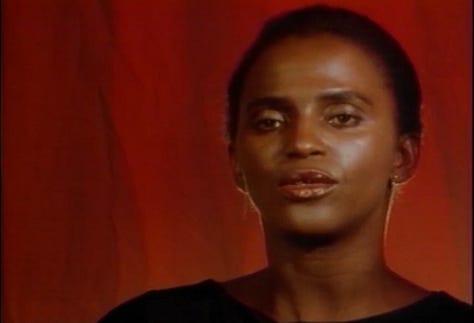

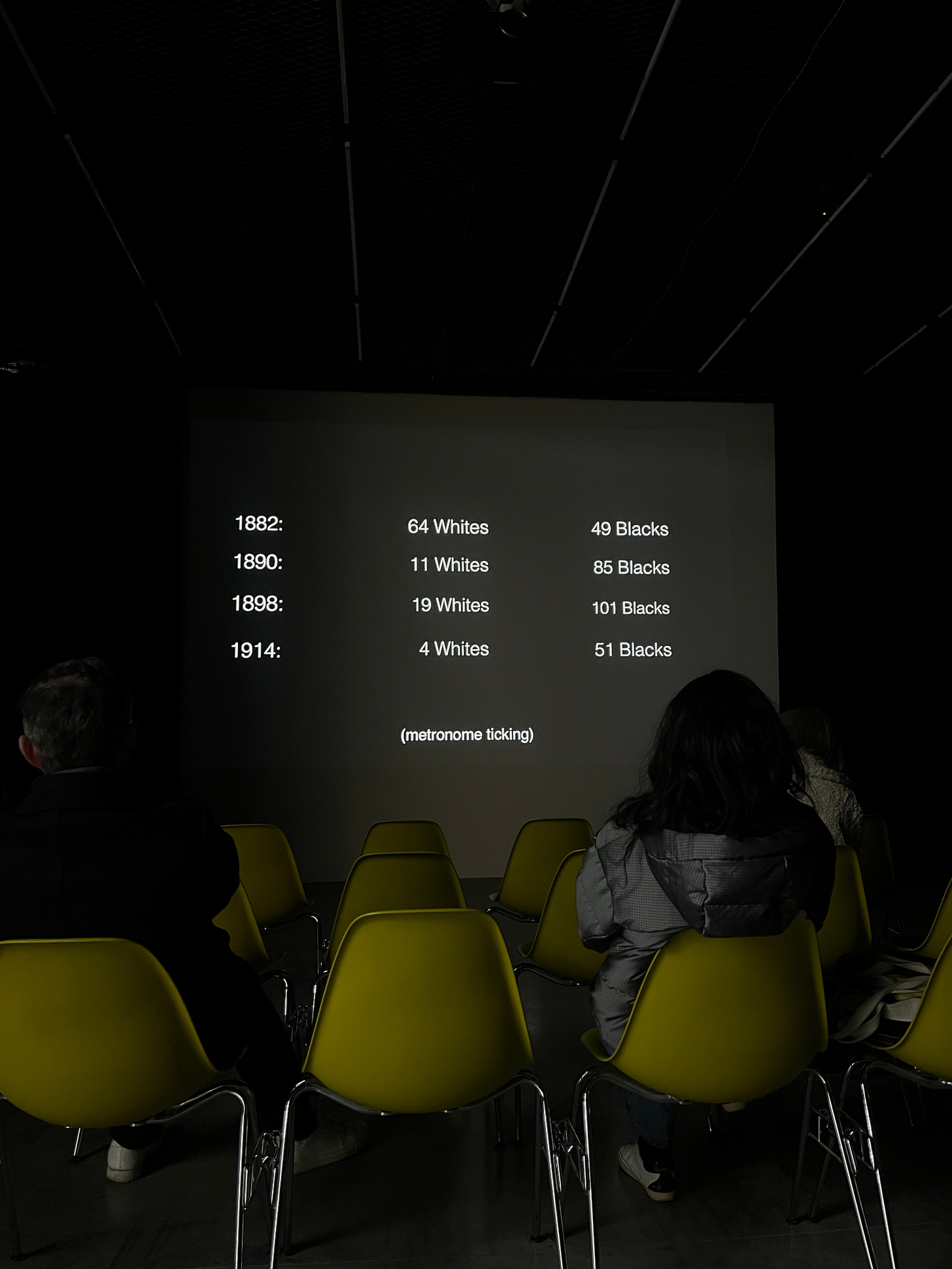

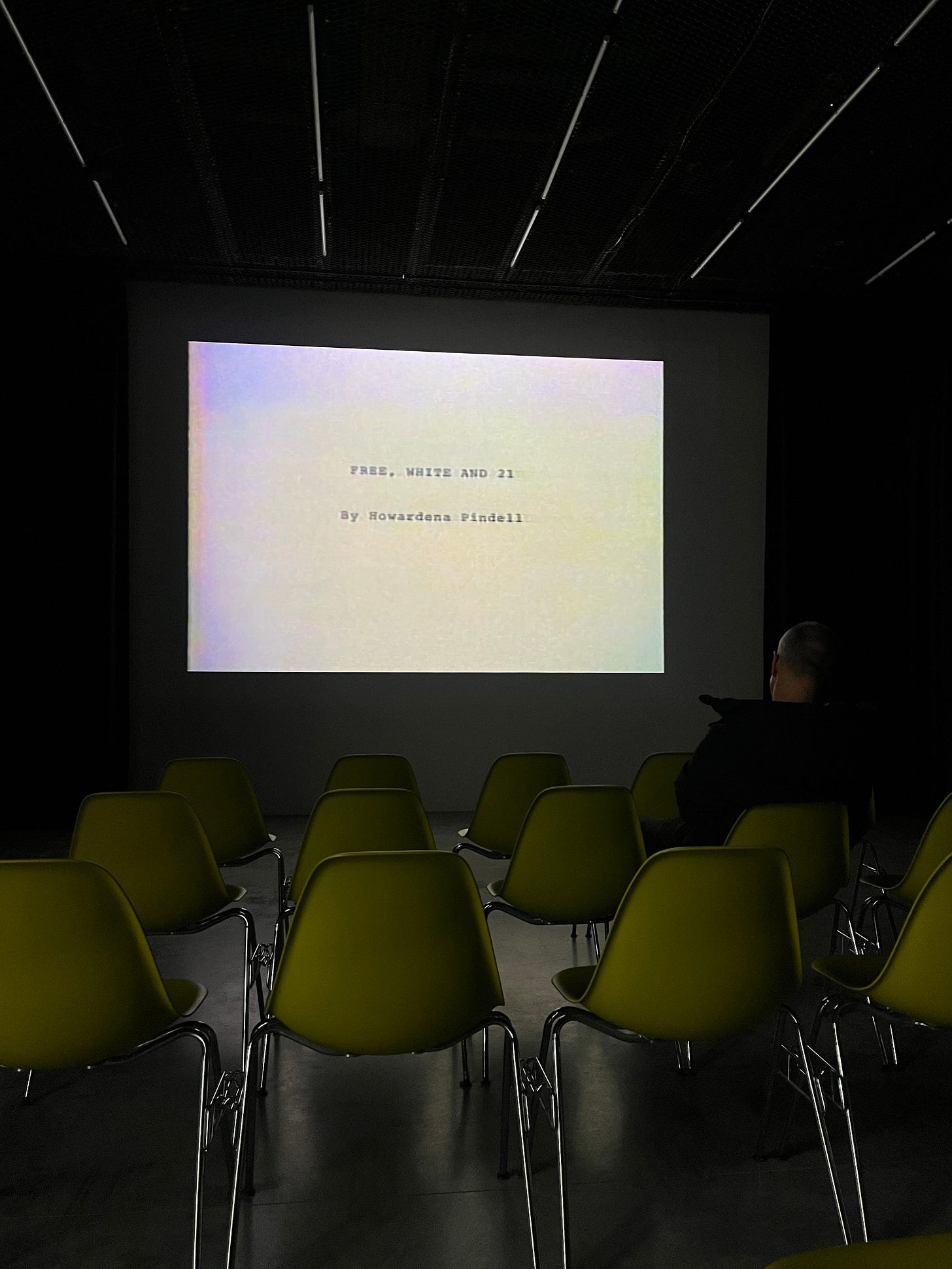

That feeling, loosely, didn’t end there. I made my way to White Cube gallery the next day to see African American painter, mixed-media, and abstract artist Howardena Pindell’s solo exhibition Off the Grid. Including her large-scale paintings, sculpture, and collage works from her career of over 60 years (extremely beautiful and innovative for their material depth, might I add), Pindell also showed three video works: Free, White and 21 (1980), Doubling (1995), and Rope/Fire/Water (2020). The curtained room showing the videos lay in the back of the gallery space with rows of neon green chairs waiting to be filled.

I came in during the middle of Free, White and 21 and decided to stay to see the entirety of each video. In each one, Pindell was very specific about her factual research and the implications of her chosen language. At certain points, she detailed a historical timeline of racial violence post-slavery, cycling through archival photographs of public lynchings of Black men and women and photographs of police and canine attacks on Black civil rights activists; listing statistics of racial terror into the height of the Black Lives Matter movement; and recounting a number of experiences of racial discrimination from her own childhood and after her years in the arts and academia.. As I sat in the room, alone at first, more and more gallery visitors came in and took a seat. I’ll note here that each one of them was white. Every time Pindell, in her videos, said the word negro, n*gger, or another racial epithet while shedding light on the Black experience, a single white audience member rose from their seat as quickly as they entered the room, and walked out silently. This happened numerous times over the course of the hour I must’ve spent watching all of the videos. Pindell, through the screen, looked back at them, too, watching their white bodies move through and inhabit an already contested arts arena with a politics of disacknowledgement. I squinted my eyes in skepticism of their avoidance, walked back through the entire gallery once more for good measure—or maybe to stake my claim on the exhibition’s subject matter—and left with a sort of burning fire inside of my chest.

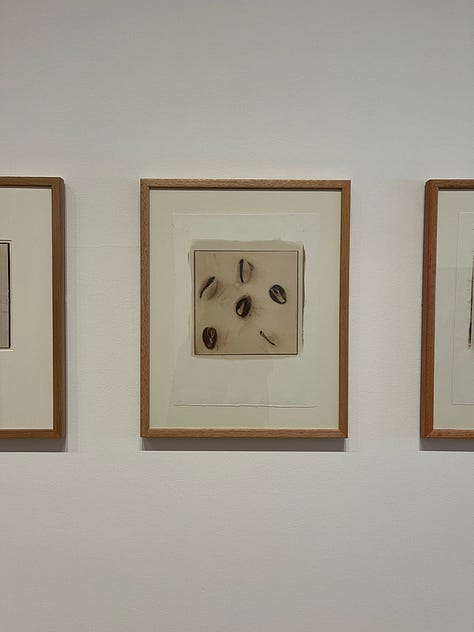

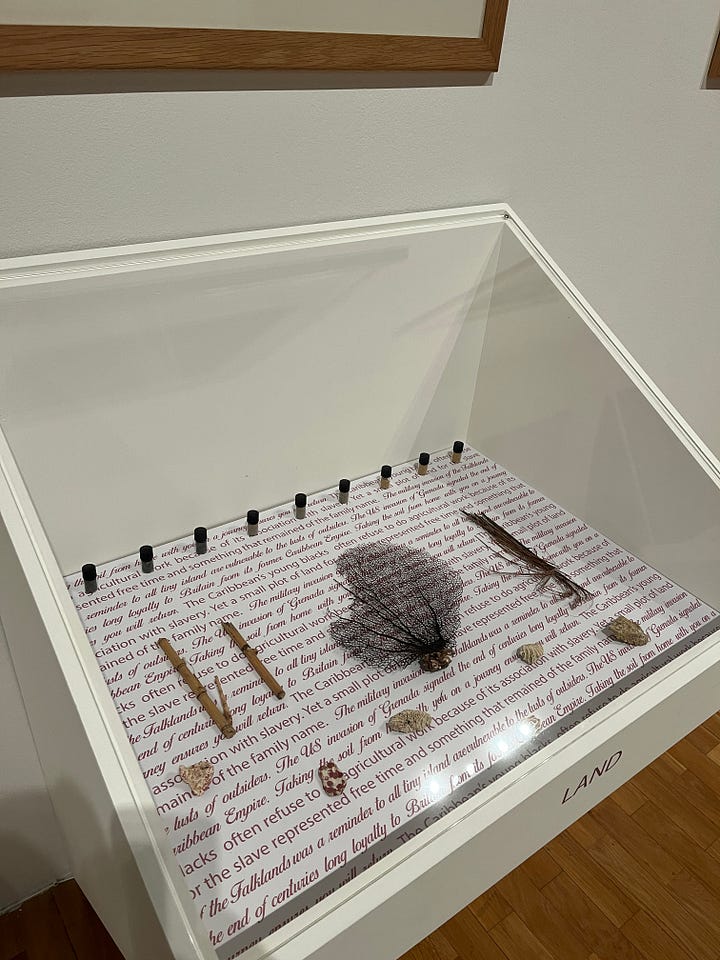

Another exhibition I saw was Joy Gregory’s Catching Flies With Honey at Whitechapel Gallery, her first major survey show, with her work exploring identity, history, race, gender, and societal ideals of beauty. Some views from that are below:

PHOTOS

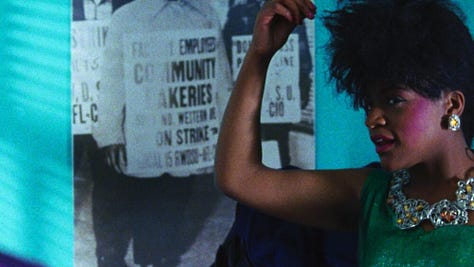

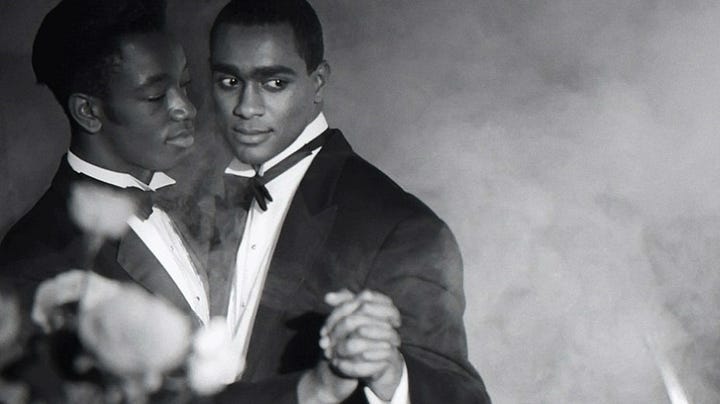

I feel that it is a rite of passage since being in the UK to declare that a new favorite Black British artist of mine has become filmmaker Isaac Julien, whose work I saw in the past couple of days at the British Film Institute. His cinematography and storytelling feel so fresh to me; even just visually, he’s introduced such unique imagemaking qualities to me, which is why I’m appreciative of his work. The films I saw were The Passion of Remembrance (1986) and Looking for Langston (1989), which can be watched free online here. Julien was also a co-founder of the Sankofa Film and Video Collective with a group of London art school students who sought to create space for the depiction of a multitude of Black experiences in film.

Lastly, I’ve finished a few books this month that I hope you’ll add to your list:

In Another Place, Not Here by Dionne Brand

Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry by Essex Hemphill

Tar Baby by Toni Morrison

Until then —

With love and gratitude,

G.

Keep that “sort of burning fire inside of (your) chest…with love and gratitude”.

This was a remarkable read, now I have to catch up and read all of them!