How to Dignify a Silhouette

Where art history's Western value system leaves the Black figure.

Last weekend, I found myself back in an antique store, reunited with the same love for found objects that began my long summer. A hole-in-the-wall shop, unassuming upon entry, caught my eye on the street corner of a Cape Town suburb. I entered warily; this one was not set up like the previous Atlanta-based store that cemented itself in my dreams in late May. Rather than booths curated by expert antiquers, I was instead plunged into a darkness, an expanse of walls revealing to me that the space was larger than I had anticipated. Dim lighting made everything appear brown, the brownest of browns, like my grandmother’s old living room. At first, I wanted to enter without expectations, and for the most part, I’d say I did. I couldn’t quite make out the different sections, though I noticed fine jewelry by the register and a collection of old vinyl records on an adjacent table. I was first drawn to a corner of books. High stacks toppling over one another - nearly falling off the shelves in excess - while a petite white woman did her best to reorganize.

I had a thirst to find some poetry, an anthology, or maybe a modern collection of a similar sort by African writers. I thumbed a section that was part poetry, part religion, part translated works, and instead found endless books with the title African Poetry, but with contributing writers who were all white. Naturally, I moved on. I switched gears, moving to the art section. Knowing me, maybe it’s where I should’ve started my search to begin with. In another unsatisfying realization, I saw echoes of Gaugin, Picasso, and other European masters of painting whose names failed to move me into action. I kept looking, though.

An old Sotheby’s catalogue - Paris, September 2002 - was one of the first things I saw on a table of scattered magazines. African, Oceanian, and Precolombian Art, read the title. A faint embossing of a Tiki statue decorated the rest of the minimalistic front cover, the entire page covered in white. It was a little beat up, but I decided to give it a try. Flipping through its pages, skimming at best, I saw visuals of traditional masks, vessels, and sculpted figurines from various West African countries, some recorded in great detail. Eventually, I flipped to a spread of a white man, James Hooper, quoted expressing his desire to expand his collection of primitive art. From Sussex, UK, he said that he was making his collection from an ethnographic point of view before an artistic one.

Quickly realizing that in my hands was another piece of artistic literature placing works from the Global South in opposition, or even inferiority, to European art styles and movements, the language of primitivity in the catalogue was a litmus test for my own studies in art history. Though Hooper claimed his collection was ethnographic, I have the urge to call it anthropological: an aimless attempt to use works like those by African artists and craftspeople to justify a classification of African societies and cultures as a mere remnant of civilizations, variant to that of the Western way. The term primitive, when applied to African art, is a misnomer rooted in colonial-era biases, misunderstanding non-Western artistic traditions, and suggesting a lack of sophistication compared to European art.

As I kept flipping through the catalogue, a trend was apparent: Hooper was surrounded by European contemporaries, white artists and collectors alike, who seemed to encounter African art on pure happenstance, surprised by its display of skill while hastily citing its excellence. Painters were photographed in their studios lined with African sculpture, possessing some perverted love for the African object, while no doubt declining to consider the lives of Black and African people.

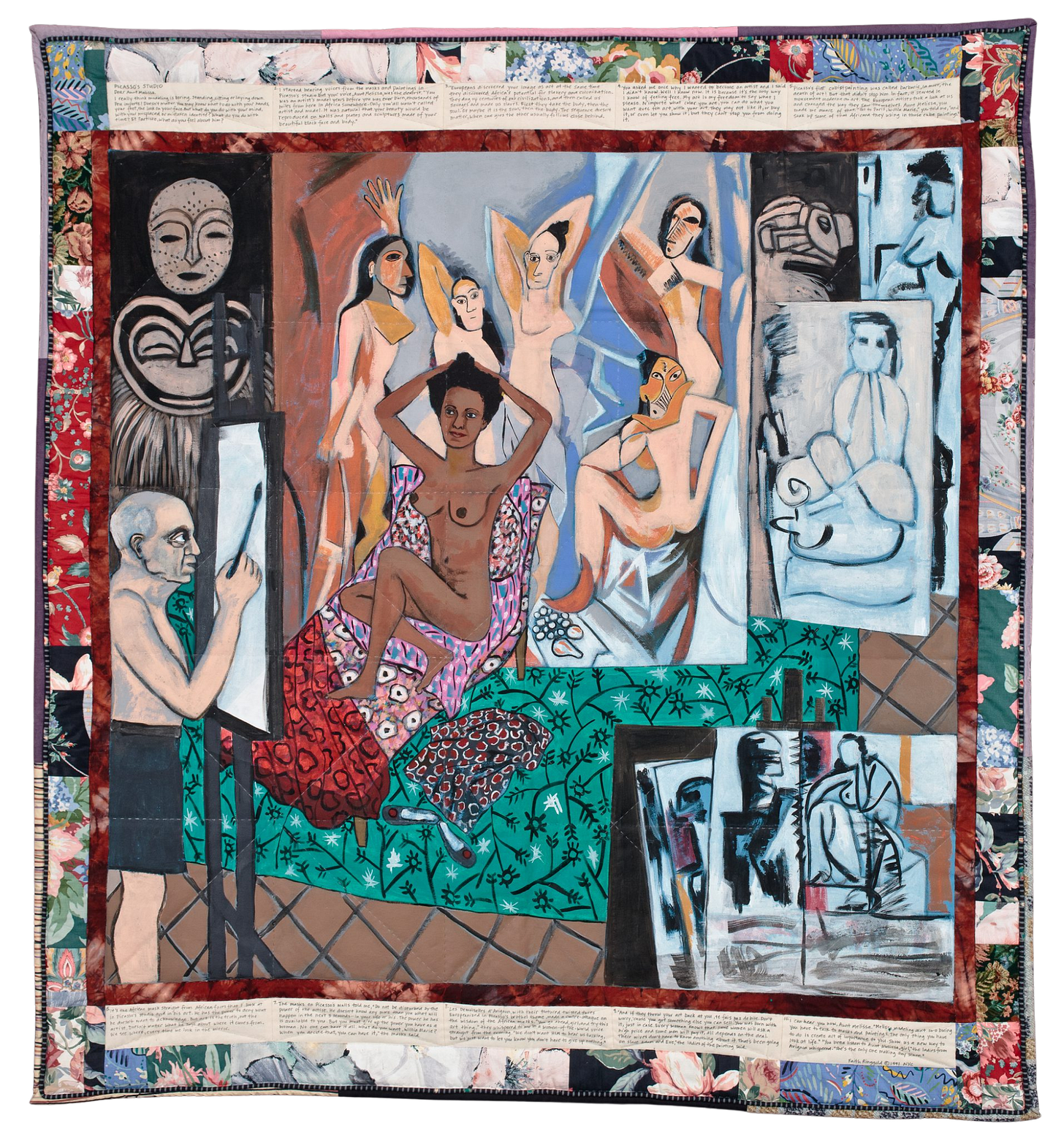

I’m reminded of an art history course of mine from the spring semester, where one day, a white professor who specialized in African art and architecture engaged us in a case study of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907).

In Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), Picasso stages five nude women in a jagged, collapsed space. Their bodies are angular, their gazes confrontational. At the time, the rawness of the nudity caused a stir, but what lingers more deeply is the way he rendered the two women on the right, faces shaped by African masks and Iberian sculpture. The influence came from the urge to capture women as emblems of distant civilizations. Picasso took from these traditions without credit, pulling from cultures seen as inferior while elevating his own artistic innovation. It’s a turning point in modern art, yes — but one built on erasure and extraction, drawn from what Europe called primitive to forge the new, never acknowledging the asymmetry of that exchange.

The Western impulse of aesthetic extraction that decontextualizes African symbols, forms, and cosmologies is well-practiced. Picasso and his contemporaries said they “discovered” African art at Paris venues, which functioned to celebrate the achievements of the 19th century and aimed to showcase advancements and inspire development for the next. One always must ask, and already knows the answer to a simple question: how did African works end up in the Paris venue? These artists encountered African art through colonial encounters and became so enamored with it at once. Acts of institutional theft allowed for the sudden materialization of African art in the minds of white artists, while the relevance, skill, and necessity of African art were initially dismissed by artists like Picasso in this period.

What does it mean to classify the Black body?

While ideating for this essay, I found the book Negro Types (1931), part of the series Seen by the Camera, published by British publisher George Routledge. It’s a small book, 64 pictures total, with a four-page introduction, hardly preparing the reader for the ensuing content. The very first paragraph writes of “all the races living in Africa,” aiming to “show the principal characteristics of the aboriginals by means of carefully selected types.” The author goes on, speaking of how African peoples’ slow influence by civilization, the “fleeting” good looks of African woman, and “the refinements of love so common in civilized countries [that are] entirely strange to the negro.” Already, Blackness is yet in a primitive condition. The following pages list different “types” of African men and women, some by region, societal status, or lineage. The accompanying photographs take up entire pages centered on Black faces in profile, ¾ view, or straight on, almost like a mugshot. Naked women and children were oggled by the camera, their figures eroticized to the point where a question of permission or consent is obviously absent. They have been posed, forced into stagnancy, and have had their land intruded upon.

In the digitally accessible version I found, the visual contrast is so high that the people’s faces are not even fully visible. Bodies and faces melt into a sea of intelligible black silhouettes, with their ascriptions, tags, and “types” the only things available to mark their identity.

The use of photographic technology sought to make the Black body visible in harrowing ways even beyond this publication. Like these, images of Black people at the hands of white photographers functioned as racial “types” in their purpose of classifying Blackness as a form of noted deviance. The perceived exoticism and abnormality of the Black body were pervertedly admired and despised. Again, in an anthropological effort of tracking the progress of Western civilization, the type functioned as a generalized depiction of a racial group—an abstraction that, while not always the ideal, conveyed the typical form or traits associated with individuals in that group.

In race scientist Louis Agassiz’s first encounter with a Black man, he wrote, “. . . Nonetheless, it is impossible for me to repress the feeling that they are not of the same blood as us. In seeing their black faces with their thick lips and grimacing teeth, the wool on their head, their bent knees, their elongated hands, their large curved nails, and especially the livid color of their palms. I could not take my eyes off their face in order to tell them to stay far away.”

Photographs have the potential to hold the soul of the sitter, capturing a moment in time wholly manipulated by the cameraman. In Negro Types, photographs were an archive, aimed to freeze the image of the Black in time as an evolutionary “other”; fixed as not white, and therefore, not human.

Rereading the introductory note, one is reminded once again that the Black subject was not an anthropologist’s - or artist’s - type. Type as in the subject of interest outside of exploitation. But I’d also like to remind us that the typified image of the Black body does not, and should not, belong to the emerging white artist or scholar to use for their professional development.

In front of or behind the camera, then, one might consider what succeeds, or subverts, the denigrating “type.” Think of your traditional portrait: the hope of capturing one's likeness and amplifying humanity, getting to choose your own pose, the adrenaline after the photo is taken, and an intense excitement to be remembered. That is the heart of the portrait: remembrance.

Cauleen Smith’s film Drylongso (1998) follows Pica, a young Black art student in Oakland who carries around a bulky Polaroid camera, photographing the Black boys and men in her neighborhood. She tells people it’s for a class project, but it’s more than that. Pica is building a personal archive of the people she sees disappearing, both literally, through the rising deaths of young Black men, and figuratively, through the everyday violence of erasure. She senses that these boys and men — her classmates, neighbors, strangers — are being made into abstractions, typified by the state. But she doesn’t photograph them that way.

She sees them in their backward caps, hoodies pulled tight over their heads, shiny sneakers, lopsided grins. These details matter to her, not as symbols to decode, but as real traces of real lives. Her portraits are not about spectacle or anthropological distance. She isn’t trying to make her subjects legible to a white gaze or fit them into the genre of documentary objectivity. She’s building a library of her own, rooted in intimacy and memory. Rather than let the Black boys and men fade into the blackness of empty memory, she photographs them as a kind of holding on.

For Pica, photography becomes an act of resistance. She knows her photos are life-and-death totems. Time slows. The ordinary becomes sacred. Her camera reframes the way we see Black men—not as already gone, not as inevitable victims, but as present, alive, worthy of being remembered in their full complexity.

In many ways, Drylongso is about how Black girls and women navigate the burden of witnessing—of having to remember what the world tries to forget. Pica doesn’t let the people she photographs get flattened into an intelligible “another,” lost to violence. She remembers. She helps us remember. And in doing so, she shows that the camera can be something other than extractive—it can be a site of care, of refusal, and of mourning. But also: a place where the liveness of a community is made visible, again and again, in all its fragility and power.

I recently started reading a book of the same name, Drylongso: A Self-Portrait of Black America by John Langston Gwaltney, who went in search of "Core Black People" ― the ordinary men and women who make up Black America. The book is essentially an oral history of Black life and identity in the Northeast, filled with anecdotes, interviews, and musings from the interviewees. A Black man and anthropologist himself, he wanted to subdue traditional modes of sociology and anthropology that excise Blackness for academic speculation and intrude on communities for the sake of the textbook. In his introduction, he makes one thing clear: “The people whose voices are heard in these pages are eminently capable of self-expression, and I have relied upon them to speak for themselves.”

So, when I left that famed antique store, I also went searching for those who could speak for themselves, and I went and found their names.

Below, I present to you some of my favorite artworks and artists I’ve encountered while in Cape Town. Think of it as my last love letter to the city. It’s been good to me.

Until then —

With love and gratitude,

G.

Writing is art. Words, the sentences, and punctuation add color - keep contributing.

How To Dignify A Silhouette,

G, your work is excellent! I will return for second viewing and reading to honor and tag notes for a qualitative material response from the indicative work you have curated matters. I want to review what resonated with me streaming through your work.

It’s impossible to write my best without chronologizing the resonant material African culture and art which you have formatted evidence of How To Dignify Silouette in the hands of foreigners’ aligned through western lens of photographical delicacy but hating the African presence. Immediate contradictions run across the continuum can't be avoided or ignored by Western invaders and plunders as you alluded in the Art of “How To Dignify Silouette.” I got it!