Shadows of the Field(s)

The women in my family all have the same hands. They signify a labor of love.

my dreams, my works, must wait till after hell

by Gwendolyn Brooks

I hold my honey and I store my bread

In little jars and cabinets of my will.

I label clearly, and each latch and lid

I bid, Be firm till I return from hell.

I am very hungry. I am incomplete.

And none can tell when I may dine again.

No man can give me any word but Wait,

The puny light. I keep eyes pointed in;

Hoping that, when the devil days of my hurt

Drag out to their last dregs and I resume

On such legs as are left me, in such heart

As I can manage, remember to go home,

My taste will not have turned insensitive

To honey and bread old purity could love.

My grandmother calls us Mitchell girls, an ode to her maiden name. All Mitchell girls, so far, have slender fingers, naturally long nails, and a birthmark or two on the backsides of both. With nearly darkened knuckles, we all opt for a subtle shimmer as our nail polish color of choice; magentas and deep ceruleans seem to be my grandmother’s favorite. We compare our hands instinctively: waiting patiently at a stop light or making our way through a backed-up queue, if I place my hand out for inspection, every Mitchell girl knows to quietly do the same.

I look at mine first. A beauty mark lies on my index finger, freckles on the top of my right hand, and an inkblot-shaped patch of darker melanin on my left. I wear a couple of rings I’ve collected recently. With only 19 years of living under my belt, my hands are soft to the touch. My mother’s hands are next. She looks between our hands, and fixes her face in a scrunched up expression when she notices the differences in our nailbeds. “Yours looks like that because you haven’t been washing dishes for 40 years,” she says. My initial reaction is to defend myself — I do the dishes too! — but I stop. She’s right. The extra roughness on her palms and the slight wrinkles revealing her veins match the same ones on my grandmother’s hands. The same hands that raised many more Mitchell girls, cooking meals from scratch to be table-ready at 4pm every evening without fail. But before that, they were hands that couldn’t go about six hours without finding something to vacuum, wipe down, or rearrange. And before that, they were hands that worked night shifts at Picadilly and morning shifts on the scalps of tenderheaded little girls who sat between her legs waiting for their hair to be done.

A certain quote is often misattributed to the likes of James Baldwin, Eartha Kitt, or even your around-the-way internet personality: “I have no dream job. I do not dream of labor.” Within its complicated quotations, the sentiment is unchanging. An intended critique of the American dream and the attractive faces of capitalism, I’m called to think about the different types of labor lingering in my own lineage. Where hands have been made rough out of force, yet endure the touch of another out of a persistent longing for community. Labor comes in many forms, but when I look at the past as prologue, I think of hands at work.

Cotton, according to Google, is “a natural fiber derived from the plant genus Gossypium [and. . .] a soft, fluffy substance primarily composed of cellulose, which is then spun into yarn and woven into fabric. Cotton is a key agricultural commodity, providing both fiber for textiles and food for humans and livestock.” Found in nearly every corner of the world, it has become as natural to living as life itself. That soft, pillowy fiber. Those bolls of cellulose that in their multitudes substantiated centuries of slavery-backed economy. A mere material that wrote down history because of its enthralling appeal. One can’t go anywhere without recognizing it, or buy anything without feeling it.

Winslow Homer was a 19th-century American landscape painter and printmaker. After the Civil War, he painted rural African American communities, especially workers, in Petersburg, Virginia. The Cotton Pickers (1876) hovers in the strange quiet of dawn — an hour heavy with beginnings and the weight of what never ends. Two Black women rise from the cotton-strewn earth, not so much standing as suspended, their dark figures haloed by the morning light and the endless pale sea of the crop. The scene is soft, almost too soft; romantic in its stillness, almost devotional in composition. One woman brushes a plant as if caressing a wound, the other gazes past us, past the moment, into a horizon that remains out of reach. Their poses, tender and deliberate, resist the expected marks of labor: no bent backs, no torn fingers, no sweat. Yet, everything about the image aches.

Their sacks are full, but the field stretches on, boundless, unyielding. The cotton clings to their aprons like memory. Fluffy, yes, but hiding the burrs beneath. Their beauty is undeniable, almost idealized, and yet it is a beauty marked by grief. The woman on the left bears an expression that holds too much: defiance, sorrow, distrust, each layered over the quiet disbelief of a freedom that has changed little. These women are no longer enslaved, but they are not yet free. They remain rooted in the same soil that once owned them, their stillness a metaphor for the false promises of progress.

A suggestive beauty and tragedy exist in ambiguity. Homer’s work is an indictment. He renders these women with grace, but also with a knowing that their labor is both majestic and tragic, unfolding in a country still unable to imagine them beyond the work they were forced to inherit. The haunting rows of cotton are a choreography themself, aiding and abetting the Black imperative to fall in line. Caught between emancipation and endurance, they become symbols of an ambiguous America: beautiful, burdened, and forever unfinished.

When teaching this painting in an art history class, a professor of mine explained that when Homer (or another of his contemporaries) was questioned about their impetus to primarily paint African American subjects, and specifically in The Cotton Pickers, African American women, the exchange went something like this:

A white countryman: “Why are you painting those dreadful creatures instead of the pretty ladies in our town?

Homer-like artist: Because they are the prettiest.

Pretty as they certainly are, Homer also found beauty in the women’s ginger handling of a material that catalyzed their future in an inevitable cycle of labor. And this is not to suggest that labor itself is utterly beautiful, but rather, I’d like to remind us that a future in the same timeline created a potential for a different beauty lying in those working hands. King Cotton is only a starting point in the middle of history.

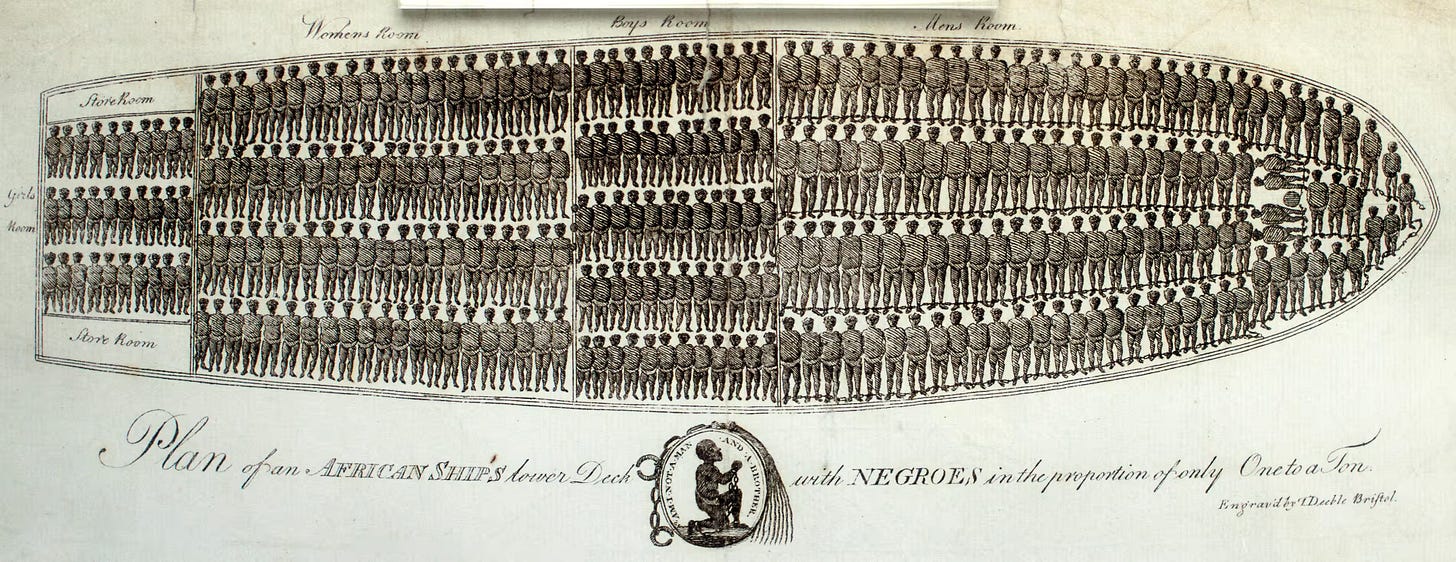

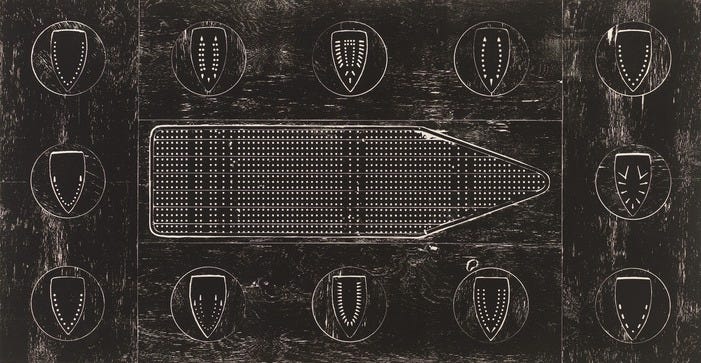

Some weeks ago, I burned myself with an iron. At the sound of burning flesh — a short sizzle — I jumped, took a breath, and took a look at the scar forming on my abdomen. I was disappointed in myself, briefly, for my clumsiness, but my second thought was to call my mother. She had a similar run-in with an iron, the whole face of the flat side burning her on the outside of her calf. Imagine its mark. Now, we share the same one. Looking at my new scar daily, I was reminded that the image of iron’s face and its related materials (e.g., the ironing board) are eerily similar in shape to the cut-away diagrams of slave ship interiors. The holes releasing the iron’s heat mimic cramped Black bodies stacked in transport across the Atlantic.

As the iron and ironing board evoke slave ships with their flattened image, with my mother and me in mind, they also evoke Black women’s domestic labor. Their relatedness is no coincidence.

Black labor in the household was simply a change of location. Rather than be overworked in the cotton fields, the kitchen, the laundry room, and the home at large became environments of intimate deprecation. The ironing board, as a traditional symbol of working-class Black women who labored as laundresses and maids, signifies the continuing burden of slavery’s sites of injury. Scenes of assembly lines of women pressing and hanging garments made with that precarious fiber their ancestors knew so well come to mind. These household objects hold pain. Hands reaching for a pot or pan, spices and sugars, was not from a desire to provide — not the same warm particularity of Black family meals that I know now or the bonding I felt when my mother taught me to iron my own clothes for the first time — but instead a notion that the domestic was dangerous. The slip of a finger, a delay in action, at the mercy of a white family’s choice of punishment. How do we find beauty here?

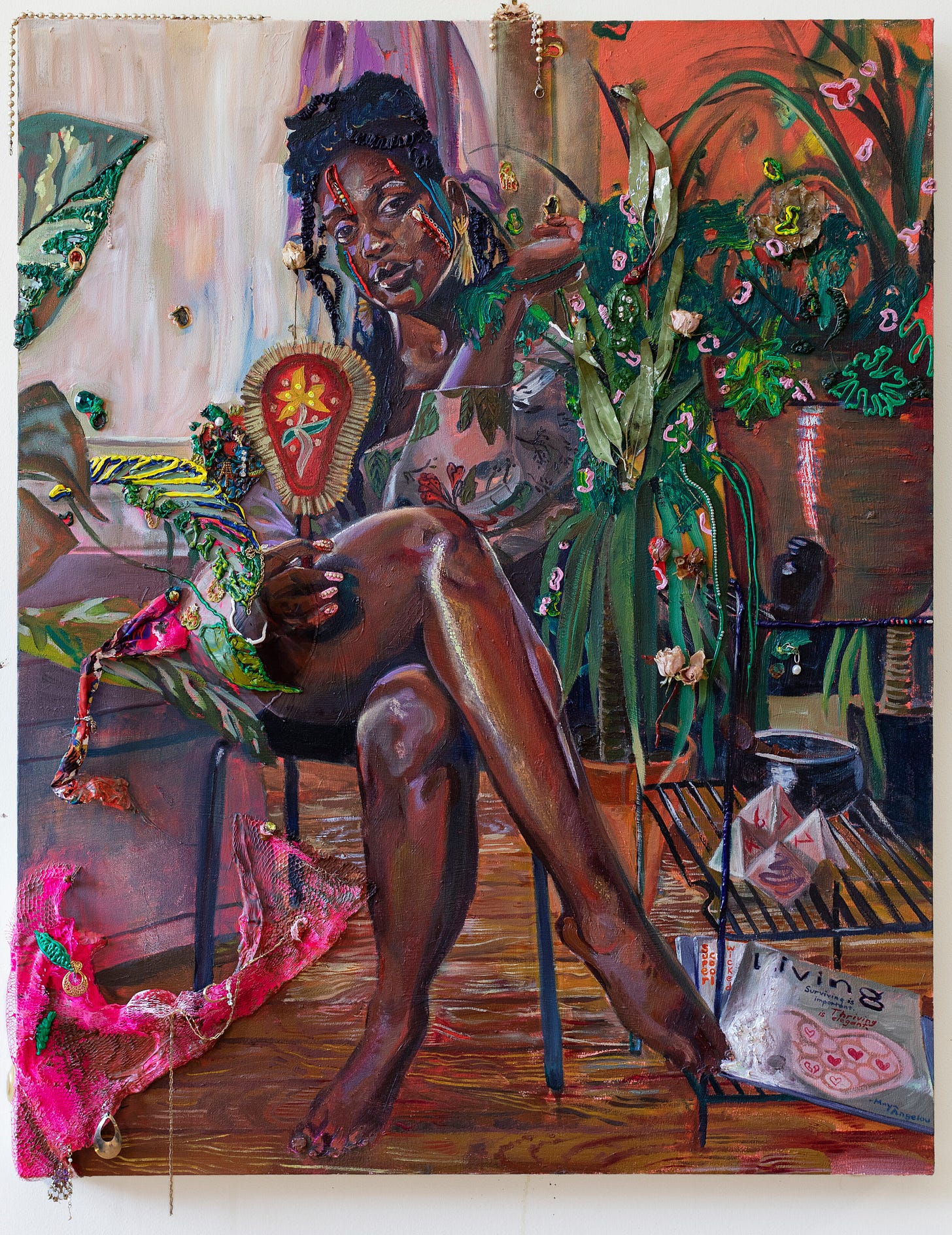

Uncommon to many Black vernacular spaces, the kitchen is a landscape imbued with multivocality. Histories of forced labor live here and will not be forgotten on account of my memory, but my grandmother’s sweet potato pie recipe lives there, too, along with wash days where I strained my back and neck over the kitchen sink; and the formula for a perfect silk press (thick globs of Blue Magic and too-high heat lathered onto my scalp); and getting my hair brushed, tugged, and pulled at the dining room table by my auntie’s heavy hands; and card games before Thanksgiving dinner; and dancing in front of the refrigerator; and all of the household ambiguities that reveal their beauty in the kitchen’s interior.

“We Own the Night”

by Imamu Amiri Baraka, 1973

We are unfair

And unfair

We are black magicians

Black arts we make

in black labs of the heart

The fair are fair

And deathly white

The day will not save them

And we own the night

Black hands make magic, finding breath in the silences of existence. I am blessed today to think of the ways I choose to use my hands, whether that be through the making of my own art or the physical experiences I make sure to populate my memories with. Because I know that the hands of my Black elders hold more than just wear and tear. I know that Black hands have created worlds out of absence, have molded visual and cultural languages where words weren’t quite enough. In Alison Saar’s Reapers, shown previously, the five enslaved women wield tools for harvesting crops: a sickle, hoe, machete, knife, and bale hook for rice, indigo, sugarcane, tobacco, and cotton. They hold these tools as if they are poised for a fight for their freedom. But what I keep discovering is that maybe those tools can also be my grandmother’s old book of Negro spirituals. Or my first sewing kit. Or my grandfather’s old playing cards. Or even the paintbrush I kept from my childhood. In Cape Town, South Africa, today, I saw Black marimba players who invited me to make beautiful noise with them on the same grounds built without Black bodies in mind. Wielding materials saturated with the spirit of determination, I see Black hands at work here, too.

Baldwin may not have dreamed of labor, and maybe I don’t either, but the capacities for what my labor looks like have blossomed into a fruitful life’s work.

In my dreams, I am dancing; the kitchen floor is my stage, my attempts to avoid steel appliances part of a nonsensical choreography of freedom. Maybe I transition to the dining table, feel a familiar marble tabletop like a bridge to the nearest window. That window leads me to the living room. I glide upon the softness of couches and loveseats, take a break to analyze the nearest vintage rug, then finally saunter down the hallway to my bedroom. In my dreams, I can’t tell that the home I traverse in dancing movements belongs to me. There are no obvious displays of my loved ones, my taste in interior design, or oddly placed trinkets, living documentations of wherever else life decided to take me. Even then, I recognize the potency of my presence through how my hands glide past each wall, remembering Black hands past, present, and future who will make it all worth it. A hug at the front door, a dap-up at the back, the kitchen table a collage of food-making, art-making, and memory-making all at once.

One day, I will look down at my own hands and feel honored that they look like my mother’s. What a long way we continue to go. A labor of love, indeed.

Until then —

With love and gratitude,

G.

Another beautiful piece, truly. GMB, the woman you are!

ur writing is beautiful omg💓✨🩷❣️🐞i wld love if u cld feedback my piece as i’ve started writing again also i was thinking to have a writers chat wld be fun so let me know if u wld wanna be a part of it🙂↕️🙂↕️💓